Chapter 5: the swapchain

In the previous chapter, we discussed how to use the graphics pipeline to produce an image. This is sufficient for offline renderers, where images are rendered one-at-a-time. However, for games and other live applications, we want the renderer to run running continuously, streaming the images it produces directly to the screen. Critically, the renderer may be working on several images in parallel; the tricky part is to enable it to do so without overloading the GPU or duplicating all resources. As we will see, bridging the gap to real-time rendering is not overly difficult: the hardest parts of the Vulkan API are already behind us! Nonetheless, we should not underestimate the task at hand. Naïvely, we may think that rendering could performed through a simple while loop such as the one below:

While this is sound, the performance would be quite poor for two main reasons:

- Unexploited opportunities for parallelism: it is entirely sequential. We could be working on the render of multiple images in parallel (this can lead to contention over computational resources, so we should not overdo it).

- Costly CPU/GPU synchronization: extracting the results to the CPU and printing them to the screen takes time. The system could setup a bridge that lets the GPU communicate directly with display-mapped memory (which is probably located on the screen itself). Then, the entire while loop could be reduced to a single function call (vulkan.draw_next_frame()), which would handle everything while avoiding back-and-forths with the CPU.

The swapchain answers both of these concerns.

In this chapter, we learn how to do pipelined rendering and get the output onto the screen using swapchains. We discuss the use of the Vulkan extensions that implement this mechanism, and we describe how to juggle multiple copies of resources to avoid conflicts between parallel renders.

A. A high-level overview

A.1. Windows and surfaces

Windows are an operating system feature. As such, they are not managed by Vulkan; we create them from CPU-land. Since different systems handle windows in different ways, we use cross-platform libraries that let us manipulate them in an abstracted manner. One such library is GLFW, which supports Windows, macOS, Wayland and X11 (to a first approximation, these last two are current and legacy Linux). Moreover, this library provides a cross-platform way of handling inputs. Alternatives to GLFW include SFML an SDL, but GLFW is the most lightweight of those. We load it in a specific manner to put it in Vulkan mode: we need to make sure that it can find the Vulkan headers, and we must request some specific instance extensions when initializing Vulkan.

Once GLFW is loaded, we can create windows. From a window, we can extract a surface, i.e., a Vulkan-side view of it for use as a rendering target. Surfaces are not a native feature of Vulkan: they are defined in one of the instance extensions that GLFW requires us to load.

A.2. Swapchains and presentation

The swapchain is Vulkan's abstraction for interacting with the presentation engine, i.e., the system-side component in charge of getting images onto the display (typically, a form of compositor). The swapchain device extension introduces new functions and an accompanying queue capacity (not all queues support swapchain operations).

We create a swapchain object with a specific image type (characterized by a resolution, a format, etc). This type is constrained by surface-specific limitations (for instance, the image resolution should match that of the underlying window). We also specify a presentation mode, which dictates how the contents of the window is updated: we may render to the display-mapped buffer directly or use some form of buffering. A swapchain object is not much more than a manager for a set of image resources; at any point, some of them are effectively owned by the system, and others may be accessed by us.

To render to a swapchain image, we must first obtain write access to one of them via the acquisition function (the presentation engine returns one of the images it does not need anymore). Although we could use this image as a draw call's color attachment, rendering directly into the swapchain is limiting: it forces us to stick to the exact resolution of the underlying window, as well as to one of the formats it supports. This rules out targeting a lower resolution or high-dynamic-range rendering with non-HDR monitors, among other things. The alternative is to render into normal images, and to merely copy the result into the swapchain (a cheap operation).

The converse of acquisition is release: we mark an image as ready for display via the present function. This operation transfers the control of a swapchain image back to the presentation engine, which may freely print them onto the screen.

In summary, a frame goes through the following steps:

- Acquisition: we get hold of a swapchain image to render to.

- Rendering: we render the scene and copy the result to the swapchain image from step 1 (we may render directly into the swapchain image if we do not mind the limitations).

- Release/presentation: we release the image, letting the presentation engine handle it (it typically displays it onto the screen, though certain images may get dropped with some presentation modes, for instance if a newer image becomes ready by the time of the next screen refresh).

The Vulkan API was designed with asynchronicity in mind, and this extends to presentation. We handle synchronization manually via primitives such as semaphores (for GPU-GPU synchronization) and fences (for CPU-GPU synchronization). We use an "image acquired" semaphore to ensure that swapchain images do not get written to before the presentation engine is fine with this (indeed, the image acquisition function may actually return an image that is still being used by the presentation engine), and a "render finished" semaphore to ensure that it does not present it while it is being rendered to. We introduce a "render finished" fence in addition to the semaphore of the same name. This enables waiting for the end of a render operation from the CPU, which we use to keep render commands generation under control: we would not want to schedule those faster than the GPU can handle them.

When we render the same scene repeatedly, our command buffer typically does not change much. Nonetheless, many engines record the command buffer on every frame, since this is a cheap operation that unlocks some interesting features such as push constants, as we discussed back in the compute chapter. Most production engines record new command buffers on every frame for the added flexibility.

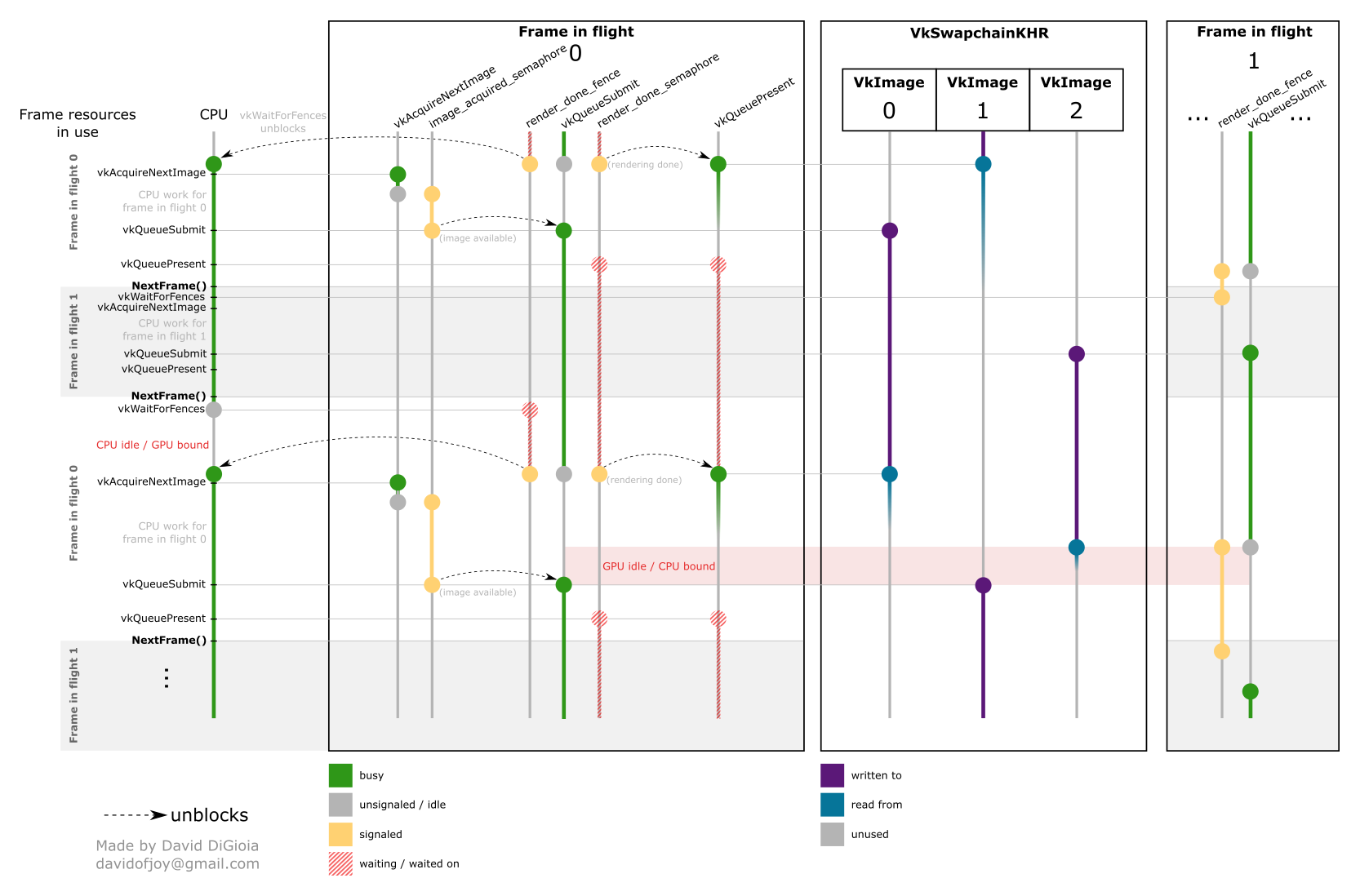

A.3. Parallel renders and juggling resources

Rendering several images in parallel can increase a GPU's throughput. There are limits to this, as all rendering tasks contend for the same physical computational resources. A common architecture supports handling up two frames in parallel (also called frames-in-flight), where frames are handled in a staggered way. That way, there are not too many computations running in parallel (we expect most of the rendering for a frame to be over by the time the next one enters the pipeline). The diagram below illustrates this method (credits go to the vulkan-diagrams project).

We must duplicate some resources to avoid conflicts. For instance, we should not have a single render finished semaphore for all the images of a swapchain: several frames may be handled in parallel, so that would be ambiguous. Resources should be duplicated as specified below:

- Per swapchain image resources: a framebuffer and a render finished semaphore (called render done in the diagram). For the latter, the diagram is error-inducing, as it seems to define it per frame-in-flight. Long-story short, the swapchain extension is quite flawed in that it leaves no way of signaling the end of a present operation, yet it is only safe to reuse the semaphores this operation waits on after it is done. We may have, e.g., three images waiting for the end of a present operation (and hogging the associated semaphores) even though our stated maximum number of frames-in-flight is two! There are two common workarounds: use a semaphore per image resource instead (as advocated here; this works because the acquisition step is guaranteed to return images that are past the present step), or add yet another extension that patches the presentation function. Render finished semaphore misuses are so prevalent in the literature that they got their own documentation page).

- Per frame-in-flight resources: a command buffer, a render finished fence (called render done in the diagram), an image acquired semaphore, the uniform buffers, and all other variable resources.

- Unduplicated resources: the rest, including the pipelines, the render passes, the vertex/index buffers, and all constant resources.

Engines that reuse command buffers should pre-record frames_in_flight_count*swapchain_images_count unique ones (this corresponds to all possible combinations of resources that we must handle; we said above that there should be one command buffer per frame-in-flight: this was a minimum, and what we should do for renderers that record on each frame). Also, in CPU-bound contexts, we can minimize input lag and unnecessary frames generation by measuring how much time is required to generate a frame, and by delaying the generation of subsequent frames so that renders finish right in time for the presentation engine.

A.4. Handling resizes

When a window gets resized or minimized, the corresponding swapchain becomes outdated. Vulkan returns either errors or warnings on later interactions with that swapchain. In that case, we must recreate it with updated characteristics.

B. A deeper dive

B.1. GLFW, windows and surfaces

GLFW is a cross-platform library that provides an interface for interacting with windows and I/O. Although it was originally developed for use with OpenGL, it supports Vulkan. This subsection uses C because GLFW is a C library, though GLFW bindings are available for all popular enough programming languages. We define a special preprocessor macro before including GLFW to let it know that we will use it in a Vulkan setting (this works for most setups; if it does not for yours, check GLFW's website):

We can then create a window (see glfwWindowHint, glfwCreateWindow and GLFWwindow):

glfwGetRequiredInstanceExtensions returns the list of Vulkan instance extensions that GLFW requires the instance to load. We must request these extensions at vkCreateInstance time. glfwGetPhysicalDevicePresentationSupport tells us whether a specific queue supports presentation.

We create surfaces from windows via glfwCreateWindowSurface (this function takes a Vulkan instance as argument; we can safely assume that the surface instance extension is one of those that GLFW asks us to load).

glfwGetFramebufferSize returns information about the size of our window (in pixels). This use of the word "framebuffer" is not related to its Vulkan meaning. Remember that GLFW also handles inputs (mouse, keyboard, etc).

B.2. The swapchain

B.2.1. Creation

Swapchains represent the device-side subsystem that handles presenting to surfaces. They are defined in the VK_KHR_swapchain device extension, which we load at vkCreateDevice time.

vkCreateSwapchainKHR creates a swapchain object for a certain image type. The choice of that image type is constrained by the underlying surface: we could not use a 1920x1080 HDR image for an old 768x576 screen, for instance. We use vkGetPhysicalDeviceSurfaceCapabilitiesKHR to get information about these constraints. We also set a minimum for the number of images that the swapchain should contain (typically, one more than the minimum number supported by the surface, as this should give us non-blocking behavior).

We may naïvely wish to immediately forward any image that comes out of our graphics pipeline to the surface. While immediate presentation is an option, it leads to tearing (the screen may refresh while the image is being copied into the buffer, leaving us with a mixture of two different images). There are smarter presentation modes that avoid this issue, but they come at a cost paid in input delay and/or performance. For instance, we may use double buffering, i.e., use two different buffers that we render two in an alternating order. One of these buffers is used for rendering while the other is bound to the display, and the presentation engine can swap the role of the buffers around. Vulkan surfaces have a notion of vertical blanking intervals, during which we are guaranteed that the display will not be refreshed. To avoid tearing, the presentation engine only swaps the buffers during such intervals.

Luckily for us, we do not directly control how the images are sent to the screen. Instead, the surface instance extension (required by GLFW) defines a set of presentation modes, which correspond to policies that we pick from when creating the swapchain. The presentation engine does all the hard work. The vanilla presentation modes are:

- Immediate: images are sent to the screen directly. May lead to tearing.

- Mailbox: multiple buffering with synchronization during the vertical blank. No tearing, but wasteful (when we produce frames faster than the presentation engine consumes them, the presentation engine only uses the latest one and discards the rest: any Watt used to produce them is a Watt wasted).

- FIFO: multiple buffering with a queue, newer results get pushed to the back. No tearing, but may lead to input lag. This is my favorite option, and also the only one guaranteed to be supported.

- Relaxed FIFO: same as above, but if a vertical blank comes before a new render is ready, the next image is sent to the screen immediately. Avoids stalling, but may lead to tearing on rare occasions.

To create a swapchain, we must also specify a color space. Only VK_COLOR_SPACE_SRGB_NONLINEAR_KHR (sRGB) is defined in core Vulkan, but extensions provide other options (see all available values). To display raw HDR data to an HDR display, we must use a color space larger than the default alongside a large image format.

Additionally, we must specify whether the contents we write into the swapchain's images are transformed in some way relative to the presentation engine's default (Khronos has a sample on the topic; it contains helpful illustrations). For instance, when we rotate a mobile device, we should render the scene in such a way as to match the new state of affairs. From the perspective of the screen, rotations change nothing: the coordinates of pixels are constant. It is up to us to adapt. For this example, there are two ways we could go (let's assume that the device went from its default portrait orientation to landscape mode):

- We could be bad citizens and build a new swapchain with images oriented so as to fit classical expectations, i.e., so that the origin of swapchain images corresponds to the top-left of our render. In other words, we could put the swapchain itself in landscape mode. However, this would make the presentation engine's job harder: instead of just copying the swapchain images onto the display's buffer, it would also have to rotate them along the way. Some devices can do this very efficiently, but for others, this can be a costly operation. In this case, we set the transformation to VK_SURFACE_TRANSFORM_IDENTITY_BIT_KHR (like for non-mobile devices).

- We could play nice with the presentation engine by leaving the swapchain in its default (portrait) orientation and writing pre-rotated images into it. This is just a matter of updating our MVP matrix to take the device rotation into account. When we do that, we must set the transformation to the same value as the surface's currentTransform to tell the presentation engine that we already took care of things (we can get this via vkGetPhysicalDeviceSurfaceCapabilitiesKHR).

Outside of mobile devices, transformations are not really a thing; we can safely set the transformation to VK_SURFACE_TRANSFORM_IDENTITY_BIT_KHR and leave it at that (see available values).

Furthermore, we specify whether we allow Vulkan to discard rendering operations that fall into pixels that cannot be seen (e.g., when another window partially hides our application). We do this through the clipped field. We almost always leave this to VK_TRUE in practice, save for the rare cases where we need to read from the images we render.

Finally, there is an oldSwapchain parameter that is meant to accelerate swapchain recreation. More information in the next subsection.

B.2.2. Recreation

When an application's window is minified, resized, rotated or moved to another screen, the characteristics of the associated surface change, and the swapchain becomes outdated as a result. When we try to acquire or present an image using an outdated swapchain, we end up either with an error code alone (VK_ERROR_OUT_OF_DATE_KHR) or with a warning alongside a result (the warning being VK_SUBOPTIMAL_KHR). Swapchain creation can also fail (or succeed with a warning) if something about the underlying surface changes while it runs.

When a swapchain operation fails, we must recreate the swapchain and the resources that reference it (framebuffers, image views, and image acquired semaphores). We are not technically obligated to do anything about suboptimal swapchains (i.e., those that succeed with a warning), but it is better to recreate them and their associated resources for performance reasons. In this latter case, we can avoid the latency of a hard sync by finishing using any already acquired image before destroying the old swapchain.

vkCreateSwapchainKHR has an oldSwapchain parameter that can speed up recreation: when we pass an outdated swapchain through it, the new swapchain reuses the old's internal resources. We say that the old swapchain becomes retired, and there can be at most one non-retired swapchain bound to a given surface at any time. We cannot acquire new images from retired swapchains, but images acquired prior to a swapchain's retiremement remain valid (at least, until we explicitly destroy the swapchain object). In particular, we can use them while waiting for the recreation of suboptimal swapchains.

The swapchain part of the specification really is a mess that will probably not get fixed anytime soon:

- There is no simple legal way of destroying swapchains once we start using them — they should only be destroyed after all their images have been released, and these are only ever released when the presentation engine is done using them. However, the presentation function does not support signaling a fence to let the CPU know when it is done. In the context of a recreation, an option is to wait for the end of the first presentation operation of the new swapchain before destroying the old one, as discussed in this sample. Alternatively, many engines use vkQueueWaitIdle for this purpose. While not technically correct, this option works fine in practice (and it is the best vanilla option for destruction without recreation).

- There is no easy way of destroying render finished semaphores. Even the radical vkDeviceWaitIdle function does not wait for these semaphores; we have to insert a ghost submission that waits for them before signaling a fence. Again, many engines are not technically correct in that regard, but vkQueueWaitIdle works fine in practice.

The VK_EXT_swapchain_maintenance1 device extension solves these issues thanks to its additional fence for the present operation and its vkReleaseSwapchainImagesKHR function, which gives us a way of releasing images without presenting them. Not all devices support this extension, so we should always integrate a fallback option.

B.3. Rendering loop

We typically use a single queue that handles both graphics and present operations (present queues that do not support graphics operations are technically possible, but not really a thing in the wild).

A rendering loop is made up of the following few steps:

- Acquire an image: we use vkAcquireNextImageKHR to request an image from a given swapchain. This function is blocking, but it takes a timeout argument (in nanoseconds) to prevent deadlocks (or UINT64_MAX for an unbounded wait). The specification does not explicitly describe in which situations this function is guaranteed not to wait, but we can expect it not to for swapchains created with a minimum number of images set to one more than the nominally supported minimum (as discussed previously). We should not use an acquired image index immediately, as it only becomes valid once either one of the optional fence/semaphore arguments becomes signaled.

- Render to it: refer to the previous chapter.

- Present the result: we use vkQueuePresentKHR to present an array of images (usually of size one; we would only have more when rendering to nonstandard devices such as VR headsets). In addition to the swapchain/image index pairs (each image index is relative to a different swapchain), we provide a set of semaphores that this operation should wait for. Also, if we want per swapchain result (if we present to several of them in parallel, which we rarely do), we can provide a pointer to an array of VkResults (we can also pass a null pointer instead of this array, and check the global function's result if we do not need such fine-grained information). If we want to use a fence (as discussed previously), we need to enable the VK_EXT_swapchain_maintenance1 device extension and make pNext point to a VkSwapchainPresentFenceInfoKHR structure (which lets us pass either a fence handle or a VK_NULL_HANDLE for each swapchain targeted by the present command).

X. Additional resources

- A 2025 presentation about swapchains by Darius Bozek (video version)